London, UK: Heavy truck makers and long-haul refrigeration makers almost all tout hydrogen as the fuel of the future, at least for long-haul transport. But there are some major stumbling blocks along the route to hydrogen.

While there is no shortage of hydrogen, not a lot of it is ‘green’, which is vital if the fuel is to contribute to a low carbon agenda. Hydrogen’s environmental credentials depend on the method of manufacture, of which there are many, but only one meets the low-carbon criteria: electrolysis using solar power.

The main way hydrogen is made is from natural gas where the carbon atom is removed from methane through a process called ‘steam reforming’. This is known as grey hydrogen but involves a lot of carbon emissions. One solution is to capture those carbon emissions and store the CO2. The result is a low carbon form of hydrogen known as blue hydrogen.

Going through the entire colour pallet of hydrogen we have black hydrogen, pink hydrogen (made from nuclear, turquoise hydrogen (produced by pyrolysis of methane) and a few more. But the holy grail of hydrogen, “green hydrogen” is made by passing water through an electrolysis cell, powered with electricity generated by a renewable source such as wind, solar or hydropower. It’s green but it’s also expensive, largely because to make hydrogen you need to put in more energy than you can get out by burning the gas. Making a kilogram of grey hydrogen costs roughly $1 for a kilogram but green hydrogen is five times the price.

Using hydrogen as a fuel for vehicles in not a new idea: its been around for over 50 years. But advances in battery technology have, largely pushed hydrogen aside except for large engines and heavy vehicles, such as maximum weight trucks, railways trains and ships and high-energy use sectors such as steel manufacture

Hydrogen used when used in vehicles typically gives the same range per tank, diesel compared to hydrogen, and refuelling time is almost the same which is a great advantage over battery recharging. But there are few hydrogen fuelling stations, at least at the moment.

There is a lot of hype about hydrogen, much like the early days of nuclear that promised electricity so cheap there would be no need to charge for it. Hydrogen is no quick substitute for natural gas for example. Hydrogen is a small molecule and far more prone to leaks than methane, ruling out its use for existing home heating without an an incredibly costly upgrade of the pipe infrastructure.

Battery technology has cornered the market for cars and vans and there is already a charging infrastructure developing. The same cannot be said about hydrogen where the necessary infrastructure simply does not exist. Which is where government comes in. It is unlikely that any significant take up of hydrogen for heavy vehicles will occur without large scale government intervention to provide the infrastructure – a national grid for hydrogen.

In the UK, government thinking is unclear. There is certainly no hydrogen strategy, and little money has been allocated to the sector. Of course, this does not stop government documents about hydrogen use talking about yje UK as poised to be a “world leader in low carbon hydrogen production and use”. Part of the problem has been UK government preference for investment in “blue hydrogen” – the kind you get from natural gas, not green hydrogen. This, despite big investment by business in green hydrogen. Inovyn, a part of Ineos which produces chemicals at its Runcorn base, has long used electrolysis to produce chlorine and hydrogen. If the plant was powered by wind or solar, the hydrogen produced there would be green hydrogen but the lack of a market in the UK hinders further investment.

ITM Power, a company based in Sheffield, is among the world leaders in a slightly different type of electrolysis to that used at Runcorn. ITM Power sells its power generation units all over Europe, including at a Shell project in Cologne which promises to be the biggest green hydrogen site on the continent.

Without government support, British involvement in green hydrogen may well go the same way as the much vaunted British lead in batteries. UK battery start-up Britishvolt narrowly avoided entering administration after the government rejected a £30m advance in funding. The firm wants to build a factory in Blyth in Northumberland which would build batteries for electric vehicles and was championed by government that committed £100m to the project. The future of the start-up was thrown into doubt over fears it could run out of money after the government rejected a £30m advance in funding on 31 October. Britishvolt has since found investors.

So is green hydrogen’s glorious future all hype? Undoubtedly not, if we are to cut carbon use. Making fertiliser and steel are clearly potential big users if we are going to eliminate carbon emissions from coal and gas. Much the same applies to critical petrochemicals.

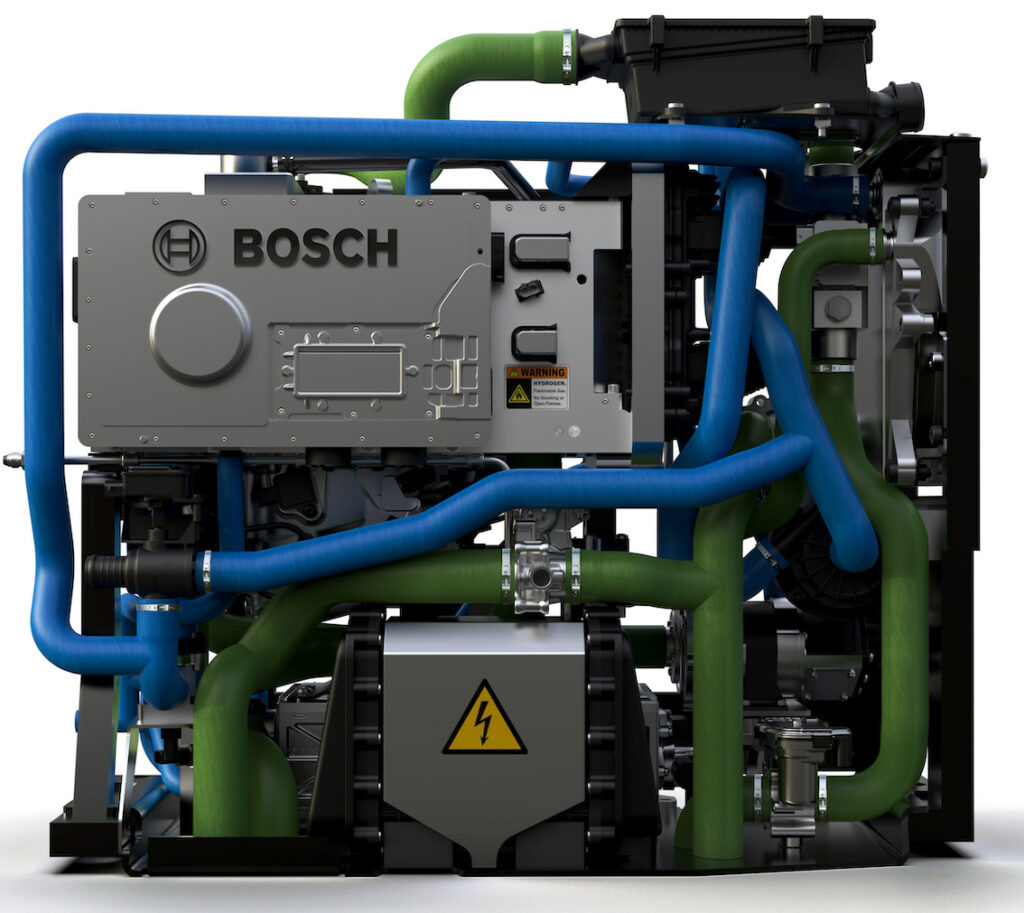

What’s lacking, in the UK especially, is the investment, vision and commitment to green hydrogen that only government can lead on. Until then, you have to travel much further afield to find new hydrogen projects, starting with China, the world leader in battery and green hydrogen technologies. And closer to home, in Germany, where hydrogen-powered trains already run on its railways, and where Mercedes-Benz expects to have the production of 40 tonne hydrogen-powered trucks within five years, and in Italy where Iveco has a hydrogen-powered Daly van using Hyundai’s 90kW hydrogen fuel cell and 140kW e-motor. The 7.2 tonne prototype, which has been tested in Europe, has a range of 350km, a 3-tonne payload and re-fuelling time of 15 minutes.

This post was amended on 1 November when it was reported that Britishvolt has averted collapse by securing additional funding. The firm wanted to draw down nearly a third of the funding early, but the government refused. It has now secured cash for the business to stay afloat in the short to medium term.